A Chronology

by Shelley Pineo-Jensen Ph.D.

Infantile Amnesia

The story goes that I was born at Doctor’s Hospital in Seattle, Washington on March 10, 1951. According to one of my mother’s younger sisters (Donna), my father was intent on naming me Jacquesborn, to herald my French ancestry. Aunt Donna and Grandma Lib (Liberty Hall, my father’s mother) were in a taxi with my father headed for the hospital. Grandma successfully argued that “Jacquesborn” is not a proper name and that it would bring me grief. So it was that I was named Shelley Jacques Pineo. The Shelley is after Percy Bysshe Shelley; my father (was enamored of) admired the Romantic Poets at that time.

My mother, Claudia, drank coffee right after I was born. She was not expected to nurse me, and I was fed from a bottle. Apparently, I was not an “easy baby” and was difficult to feed. When my diet was upgraded to the gruel babies were fed at that time (a concoction that included corn syrup and rice cereal) my mother used a nail to punch a larger hole in a baby bottle nipple. Then she propped the bottle and that was how I was introduced to semi-solid food.

My first home was a houseboat on Union Bay. It was not really a boat; it was a home on stilts built over the water. My Aunt Donna and Uncle Foster (my father’s older brother) were married and lived there too. About eight months later my beautiful cousin Michelle was born.

My father was an undergraduate at University of Washington. He worked full time in the evenings at Griffin Fuel Company, where he was the night manager. After their wild courting days in San Francisco and Berkeley, this must have seemed a very pedestrian life for the Mr. and Mrs. Ronn Pineo. According to my mother, every evening she would go down to the corner drug store and call my dad at work (for a nickel, back in the day). As she left, she would kick my crib into Donna and Foster’s room where they were sleeping to let them know they were baby sitting me. I would cry and she would run off.

My second home was an apartment in the University District. I remember only one day – moving day. The apartment was on the second floor, we moved out through the narrow kitchen, down steep wooden steps, and across the street to another second-floor apartment.

Our new home was in an apartment in a stately home that had been divided up into thirds. There was a bay window facing the street with window seats. Some of my mother’s things were packed in storage under the seats. Two bedrooms, a bathroom with a tub, a living room, a dining room, a kitchen, a laundry room, and behind all that, a door to an external staircase leading down to the back yard. The neighborhood was green, with mature trees and green lawns.

The story goes that I was born at Doctor’s Hospital in Seattle, Washington on March 10, 1951. According to one of my mother’s younger sisters (Donna), my father was intent on naming me Jacquesborn, to herald my French ancestry. Aunt Donna and Grandma Lib (Liberty Hall, my father’s mother) were in a taxi with my father headed for the hospital. Grandma successfully argued that “Jacquesborn” is not a proper name and that it would bring me grief. So it was that I was named Shelley Jacques Pineo. The Shelley is after Percy Bysshe Shelley; my father (was enamored of) admired the Romantic Poets at that time.

My mother, Claudia, drank coffee right after I was born. She was not expected to nurse me, and I was fed from a bottle. Apparently, I was not an “easy baby” and was difficult to feed. When my diet was upgraded to the gruel babies were fed at that time (a concoction that included corn syrup and rice cereal) my mother used a nail to punch a larger hole in a baby bottle nipple. Then she propped the bottle and that was how I was introduced to semi-solid food.

My first home was a houseboat on Union Bay. It was not really a boat; it was a home on stilts built over the water. My Aunt Donna and Uncle Foster (my father’s older brother) were married and lived there too. About eight months later my beautiful cousin Michelle was born.

My father was an undergraduate at University of Washington. He worked full time in the evenings at Griffin Fuel Company, where he was the night manager. After their wild courting days in San Francisco and Berkeley, this must have seemed a very pedestrian life for the Mr. and Mrs. Ronn Pineo. According to my mother, every evening she would go down to the corner drug store and call my dad at work (for a nickel, back in the day). As she left, she would kick my crib into Donna and Foster’s room where they were sleeping to let them know they were baby sitting me. I would cry and she would run off.

My second home was an apartment in the University District. I remember only one day – moving day. The apartment was on the second floor, we moved out through the narrow kitchen, down steep wooden steps, and across the street to another second-floor apartment.

Our new home was in an apartment in a stately home that had been divided up into thirds. There was a bay window facing the street with window seats. Some of my mother’s things were packed in storage under the seats. Two bedrooms, a bathroom with a tub, a living room, a dining room, a kitchen, a laundry room, and behind all that, a door to an external staircase leading down to the back yard. The neighborhood was green, with mature trees and green lawns.

There is a home movie that my brother Smith converted from old film to video. I had a copy and watched it once. Then my brother Noel talked me into letting him take it to give to our Aunt Donna. I have been unable to get any of my brothers to make me a copy . . . even though they all have a copy. I would love to get my hands on it but all I have at this point is my memory of it. That and my husband’s memory of it. He watched it several times. The following is reconstructed from both our memories.

The scene in question begins with me dancing around in the front yard. My father is probably filming. Jayne comes out the front door, unwillingly. She walks a few steps, crying, and then collapses on the ground. I go to her and encourage her to cheer up, to get up, to join me in the dance. But she resists and cries on.

So I danced away, floating like a dandelion seed on the wind. This story is a metaphor for my entire life.

The scene in question begins with me dancing around in the front yard. My father is probably filming. Jayne comes out the front door, unwillingly. She walks a few steps, crying, and then collapses on the ground. I go to her and encourage her to cheer up, to get up, to join me in the dance. But she resists and cries on.

So I danced away, floating like a dandelion seed on the wind. This story is a metaphor for my entire life.

First Memories

1952

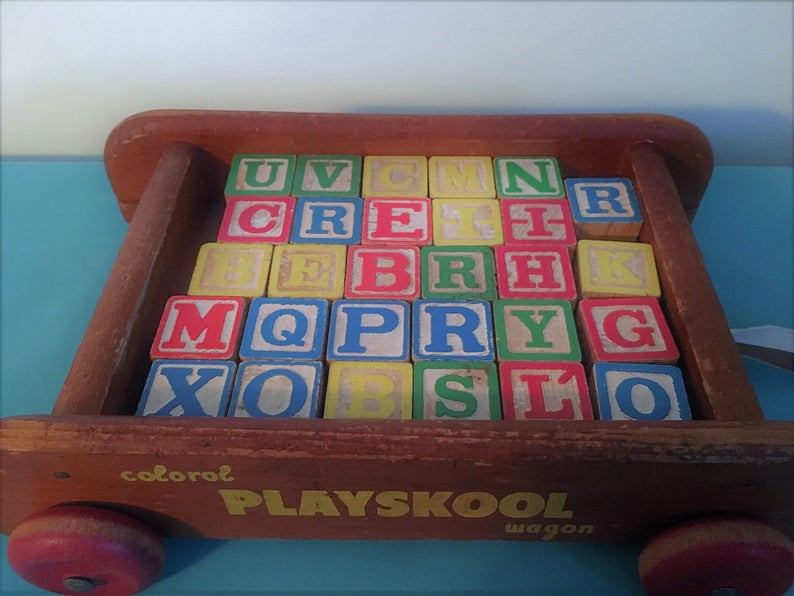

My first memory is just a mental snapshot of moving day, from my second home to my third. I remember a lot more about that second apartment. My sister Jayne was born when I was 18 months old. Her crib was in my parent’s bedroom and outside their bedroom door I found a little wagon filled with baby blocks sitting on the floor. I was very excited but was soon shocked to be informed that the blocks were not for me! They were for that little baby sleeping in their room. My thought was that she was too little to use them. It seemed like a waste of resources to me.

Eventually, most of the toys were communal, including these blocks. My parents were very good about encouraging sharing.

1952

My first memory is just a mental snapshot of moving day, from my second home to my third. I remember a lot more about that second apartment. My sister Jayne was born when I was 18 months old. Her crib was in my parent’s bedroom and outside their bedroom door I found a little wagon filled with baby blocks sitting on the floor. I was very excited but was soon shocked to be informed that the blocks were not for me! They were for that little baby sleeping in their room. My thought was that she was too little to use them. It seemed like a waste of resources to me.

Eventually, most of the toys were communal, including these blocks. My parents were very good about encouraging sharing.

1954

The benches in the front bay window were storage areas. Jayne must have at least two when she and I took my mother’s dolls out of the benches and played with them. It was early morning, before my parents were up. My mother was very disappointed that we had poked the eyes into the heads of the dolls. Unsupervised children get into trouble a lot.

The benches in the front bay window were storage areas. Jayne must have at least two when she and I took my mother’s dolls out of the benches and played with them. It was early morning, before my parents were up. My mother was very disappointed that we had poked the eyes into the heads of the dolls. Unsupervised children get into trouble a lot.

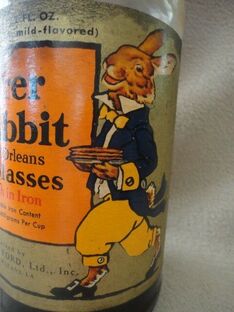

One event from my earliest memories is pivotal in my development. I was about three when I tried to convince my mother that I should get to eat some of the Brer Rabbit Molasses in the cupboard. My mother patiently explained to me that it wasn’t very tasty, and it was a cooking supply, not a treat for children. But still, I persisted. I made the compelling argument that it MUST be for children because there was a cartoon rabbit on the bottle. My mother got that twinkle in her eye and gave in. She got a spoon and poured some of that black molasses into it. I was very pleased, anticipating the sweet taste and winning an argument with my mother. Then, I tasted it.

This was a seminal experience in my relationship with my mother. I really understood that she was not ever tricking me, not trying to deprive me, and was seriously looking out for my best interest. She was on my side and she knew more stuff than I did.

From then on, I viewed my mother in a whole new light; it has lasted me my whole life. My mother was on the square with me. She was on my side. An interesting benefit for me was that when I stopped struggling with my mother for authority, I was given more agency. Because I believed her and did what she asked, I got more freedom than my siblings. At the time, I thought it was because I was the oldest, and some of my freedom was the benign neglect that infused my entire relationship with my parents, but some of the liberty to move about the world and follow my own judgement was earned respect because I took my mother seriously. She was no fool and she didn’t lie to me. If she said something was dangerous, I believed her. I didn’t always do as I was told, but I tried. My mother and father had confidence in me. Lucky me.

My life has always had a fairy tale aspect to it. My mother often told me she knew things because “a little bird told her.” She also told me more than one occasion to “follow my nose.” This is something a friendly witch would tell the young noble hearted lass who was going to find adventure and save the village. So, I have lived my life believing that birds can carry magical messages and that I should follow my own instincts about how to live my life. I would have had a life of adventure and that when called upon, I have been a leader – I would save the village.

From then on, I viewed my mother in a whole new light; it has lasted me my whole life. My mother was on the square with me. She was on my side. An interesting benefit for me was that when I stopped struggling with my mother for authority, I was given more agency. Because I believed her and did what she asked, I got more freedom than my siblings. At the time, I thought it was because I was the oldest, and some of my freedom was the benign neglect that infused my entire relationship with my parents, but some of the liberty to move about the world and follow my own judgement was earned respect because I took my mother seriously. She was no fool and she didn’t lie to me. If she said something was dangerous, I believed her. I didn’t always do as I was told, but I tried. My mother and father had confidence in me. Lucky me.

My life has always had a fairy tale aspect to it. My mother often told me she knew things because “a little bird told her.” She also told me more than one occasion to “follow my nose.” This is something a friendly witch would tell the young noble hearted lass who was going to find adventure and save the village. So, I have lived my life believing that birds can carry magical messages and that I should follow my own instincts about how to live my life. I would have had a life of adventure and that when called upon, I have been a leader – I would save the village.

Johnny and Michael

Johnny and Michael were about the same ages as Jayne and I were. They lived next door. There were no fences separating our yards.

When I was three, I was in the back yard with Johnny and Michael. We were looking into a basement window of the building they lived in. It was similar to our building – an old large home that had been converted into apartments. There was a man living in the basement apartment and he was in there. We could see him moving around.

Johnny and Michael handed me a large rock and encouraged me to throw the rock through the window. “Throw the rock through the window! Throw the rock though the window!”

So I threw the rock through the window. As fresh as if it just happened, I can hear the breaking glass, see the shattered hole in the window, then hear the yelling of the man downstairs in the basement. I ran home.

Later, I was standing in the dining room of our apartment and my mother was angry with me. She said, “Next time, use your head!” I thought, and found out later actually did say, “Do you mean break the window with my head?” I really wondered what my mother’s logic was there . . .

When Jayne and I received silver cap pistols, Johnny and Michael said they wanted to show them to their mom. They took our cap pistols and never gave them back.

I have no explanation for why my parents did not go over to get us back those toy guns. Perhaps they didn’t like them anyway. I’ll never know. But the toys were just gone, taken by the bullies next door.

A few years later, I dreamed that my mother took Jayne and me on the bus to Johnny and Michael’s new house for a birthday party. Jayne and I found the silver cap pistols and took them home with us. For a long time I believed that really happened, but my mother cleared that up . . . we never saw those nasty children again after we moved away; it didn’t happen. It seems so real but it must have been a dream.

I think there is value in re-writing the past. I DID get that goddamn gun back. . . . in my dreams.

Johnny and Michael were about the same ages as Jayne and I were. They lived next door. There were no fences separating our yards.

When I was three, I was in the back yard with Johnny and Michael. We were looking into a basement window of the building they lived in. It was similar to our building – an old large home that had been converted into apartments. There was a man living in the basement apartment and he was in there. We could see him moving around.

Johnny and Michael handed me a large rock and encouraged me to throw the rock through the window. “Throw the rock through the window! Throw the rock though the window!”

So I threw the rock through the window. As fresh as if it just happened, I can hear the breaking glass, see the shattered hole in the window, then hear the yelling of the man downstairs in the basement. I ran home.

Later, I was standing in the dining room of our apartment and my mother was angry with me. She said, “Next time, use your head!” I thought, and found out later actually did say, “Do you mean break the window with my head?” I really wondered what my mother’s logic was there . . .

When Jayne and I received silver cap pistols, Johnny and Michael said they wanted to show them to their mom. They took our cap pistols and never gave them back.

I have no explanation for why my parents did not go over to get us back those toy guns. Perhaps they didn’t like them anyway. I’ll never know. But the toys were just gone, taken by the bullies next door.

A few years later, I dreamed that my mother took Jayne and me on the bus to Johnny and Michael’s new house for a birthday party. Jayne and I found the silver cap pistols and took them home with us. For a long time I believed that really happened, but my mother cleared that up . . . we never saw those nasty children again after we moved away; it didn’t happen. It seems so real but it must have been a dream.

I think there is value in re-writing the past. I DID get that goddamn gun back. . . . in my dreams.

Ronn

I was born in March of 1951; Jayne was born in September of 1952; Ronn was born in April of 1954. We were still at that apartment, my third home. My mother had a playpen she would set up in the back yard to contain Ronn while she hung up the laundry to dry on the clothesline.

Ronn was wily and wiggled the bars until he could pull them out of place and then make a break for it. He always headed straight for the street, but he could not move very quickly. He crawled. Along with my sister, one of my jobs was to watch for the prison break and capture the prisoner and return him to the jail. My mother would use her wiles to secure the pen. We repeated this scene numerous times. I learned that I was responsible for the safety of my siblings when I was three years old.

I was born in March of 1951; Jayne was born in September of 1952; Ronn was born in April of 1954. We were still at that apartment, my third home. My mother had a playpen she would set up in the back yard to contain Ronn while she hung up the laundry to dry on the clothesline.

Ronn was wily and wiggled the bars until he could pull them out of place and then make a break for it. He always headed straight for the street, but he could not move very quickly. He crawled. Along with my sister, one of my jobs was to watch for the prison break and capture the prisoner and return him to the jail. My mother would use her wiles to secure the pen. We repeated this scene numerous times. I learned that I was responsible for the safety of my siblings when I was three years old.

Ronn fils, Jayne Monica, and Shelley Jacques Pineo actual baby pictures

2343B 42nd Avenue East, Seattle, Washington

I lived in Seattle until I was nine. Seattle is cold, wet, and gray. In addition to the normalcy of overcast skies, I experienced many kinds of precipitation: sleet, drizzle, steady day-long rain, showers, sprinkles, mist, and fog. To me, overcast cool weather with intermittent rain showers is luxurious. It is homey. I can breathe.

I lived in Seattle until I was nine. Seattle is cold, wet, and gray. In addition to the normalcy of overcast skies, I experienced many kinds of precipitation: sleet, drizzle, steady day-long rain, showers, sprinkles, mist, and fog. To me, overcast cool weather with intermittent rain showers is luxurious. It is homey. I can breathe.

April showers bring May flowers. This was true in Seattle. After we moved to the two-bedroom cottage off Union Bay, I fell in love with my first flower. It was a lovely little pale blue thing. My father told me it was a “forget-me-not.” They grew, seemingly wild, on the gate between the back yard and the path to the alley.

The next flower I fell in love with was the iris. Our neighbors on the other side of the alley had decadent deep purple bearded iris. I want very much to pick one and take it home, but my mother had instructed me that it would be a form of theft to pick the neighbor’s flowers, so I resisted the impulse, every day on the way to and from school. But I would stop and admire the beauties.

The other significant flower of my life that I learned to love in Seattle was the bleeding heart. A lovely specimen grew in the back yard in the flowerbed beneath the living room window. I loved the delicacy and the symbolism.

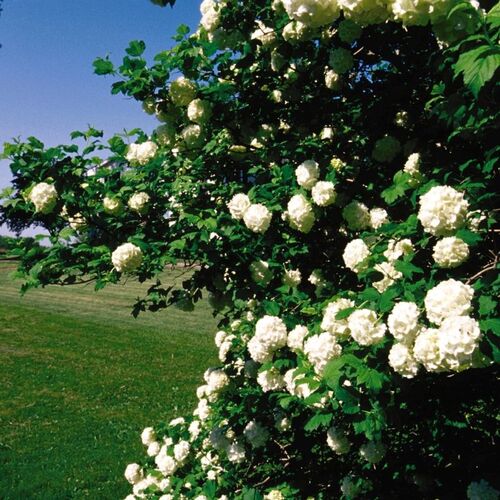

When we first moved into 2343B, the snowball tree in the backyard was in full bloom. Upon learning the name of this plant, mischief makers Shelley, Jayne, and Ronn ran over to the tree and started a snowball fight. All the adults – my parents and the landlord, erupted into angry yelling, so we stopped. But don’t worry, later on, when the grown-ups were out of the picture, we completed the snowball fight, demolishing all the lovely blooms.

The next flower I fell in love with was the iris. Our neighbors on the other side of the alley had decadent deep purple bearded iris. I want very much to pick one and take it home, but my mother had instructed me that it would be a form of theft to pick the neighbor’s flowers, so I resisted the impulse, every day on the way to and from school. But I would stop and admire the beauties.

The other significant flower of my life that I learned to love in Seattle was the bleeding heart. A lovely specimen grew in the back yard in the flowerbed beneath the living room window. I loved the delicacy and the symbolism.

When we first moved into 2343B, the snowball tree in the backyard was in full bloom. Upon learning the name of this plant, mischief makers Shelley, Jayne, and Ronn ran over to the tree and started a snowball fight. All the adults – my parents and the landlord, erupted into angry yelling, so we stopped. But don’t worry, later on, when the grown-ups were out of the picture, we completed the snowball fight, demolishing all the lovely blooms.

On that same day, I climbed up the tall evergreen in the backyard, admired the view and then climbed back down. My brother quickly climbed up into the tree a few feet up – maybe 6 feet – and then found he could not climb down. The jump was too far. So he did what children must do when frustrated and scared – he started crying, as noisy as a banshee. The landlord climbed partway up into the tree and handed Ronn down to my father. Thereafter, the edict was that I was permitted to climb trees as I pleased, but the rest of the children were forbidden. Worked for me.

McGilvra Elementary School, Seattle, Washington

When it was time for me to start Kindergarten, my mother taught me how to use public transportation to get there. I was five years old. I was given two dimes, the round-trip cost of the bus. We walked down to the corner, crossed over to the other side kitty-corner. We waited at the bus stop until the bus came. I climbed up the gigantic steps and dropped my dime into the money receptacle. We found seats and then counted the stops. Mine was the third stop. There was a cable strung along the side of the bus, above the window. Before the third stop, I had to reach up to grab it and tug on it. This sounded a buzzer and told the bus driver to stop to let me off.

We got off the bus and walked three blocks up the hill to where the school was. We went up the front steps and straight back to the crossways hall. My classroom was there, right at the intersection. We turned around and headed back; my mother pointed out the office, on the right, as we headed out of the huge dark hallway back to the giant doors and the light and the massive staircase.

We walked back down to the bus stop, crossed the busy street, with the light, in the crosswalk, and then waited for the return bus. The route was different! But I knew which stop was the right one to get off. I was proud that I was going out into the grown-up world and confident that I could manage the bus.

When it was time for me to start Kindergarten, my mother taught me how to use public transportation to get there. I was five years old. I was given two dimes, the round-trip cost of the bus. We walked down to the corner, crossed over to the other side kitty-corner. We waited at the bus stop until the bus came. I climbed up the gigantic steps and dropped my dime into the money receptacle. We found seats and then counted the stops. Mine was the third stop. There was a cable strung along the side of the bus, above the window. Before the third stop, I had to reach up to grab it and tug on it. This sounded a buzzer and told the bus driver to stop to let me off.

We got off the bus and walked three blocks up the hill to where the school was. We went up the front steps and straight back to the crossways hall. My classroom was there, right at the intersection. We turned around and headed back; my mother pointed out the office, on the right, as we headed out of the huge dark hallway back to the giant doors and the light and the massive staircase.

We walked back down to the bus stop, crossed the busy street, with the light, in the crosswalk, and then waited for the return bus. The route was different! But I knew which stop was the right one to get off. I was proud that I was going out into the grown-up world and confident that I could manage the bus.

On the first day of school, my mother and my siblings walked me to the first corner. I crossed two streets on my own and waited for the bus with some adults. There was a bench and I sat on it. My family waved to me as I got on the bus. I was actually pretty anxious about the timing on pulling the buzzer. I didn’t want to do it at the wrong time. Too soon and I would make the driver stop for nothing. Too late and he wouldn’t pull over at my stop. Also, I was too short to reach it easily, and had to climb up onto the seat. But I got the timing right, got off the bus, and walked up to the school. The walk seemed much longer without my mother there, but I got to school, on time, ready to LEARN stuff.

After a few days I discovered that some of the children who lived near me were walking home from school. One of them, Priscilla, lived across the street from me. When I got home from school, I asked my mother if would be okay if I walked home from school with the other kids. Boy was my mother happy. That twenty cents a day was a huge expense for my family. We had a washing machine but no dryer. We had no TV. I did not realize that we were poor. I didn’t figure that out until I was an adult. My life seemed rich, but I knew “waste not, want not” and “a stitch in time saves nine” and thought that we were thrifty. My time as a public bus rider was short, but it had a big impact on me. I was challenged by the experience and enjoyed it immensely.

After a few days I discovered that some of the children who lived near me were walking home from school. One of them, Priscilla, lived across the street from me. When I got home from school, I asked my mother if would be okay if I walked home from school with the other kids. Boy was my mother happy. That twenty cents a day was a huge expense for my family. We had a washing machine but no dryer. We had no TV. I did not realize that we were poor. I didn’t figure that out until I was an adult. My life seemed rich, but I knew “waste not, want not” and “a stitch in time saves nine” and thought that we were thrifty. My time as a public bus rider was short, but it had a big impact on me. I was challenged by the experience and enjoyed it immensely.

Published 3/26/20

My first teacher at McGilvra was Mrs. Rule. She taught us to say “library” instead of “lie-berry” and played the piano and taught us how to cut out snowflakes by folding up a piece of paper and cutting, just so. We sat in tiny chairs at low tables for “table work.” A large part of the room was open, with linoleum that featured large squares decorated with illustrations of nursery rhymes and fairy tales. One child sat in each square, giving us easy-to-understand boundaries and something interesting to contemplate if we were bored. During nap time we got one square to lay on, providing we had brought a nap blanket. They went home for laundering on Friday. If you forgot to bring yours back, you had to nap seated at the table with your head resting on your folded arms. After nap – graham crackers and milk. Good times.

The following year, when she got there, Jayne hated Kindergarten. She cried and had to go home on more than one occasion. I pitied her. How could she miss that there were so many more opportunities for fun. There was a playhouse! There were blocks! We planted seeds in paper milk cartons and watched them grow, sitting on the ledge of the enormous wall of windows. We painted on easels wearing Dad’s old shirt for a smock. We finger painted!

When I got to first grade, on the first day the teacher told us she had a sad announcement. Mary, one of the students who was in our Kindergarten class, had died during the summer. She was playing tag with Marvin and ran out between two parked cars into the path of an oncoming car and was killed instantly. I knew Mary. I had been to her house, about two blocks from mine, right after the Fourth of July. She showed me a mark on a support beam of a patio cover made by a pinwheel that had been driven around and around by a firework. She thought it was terrible to mar the wood like that. She was a nice ordinary little girl.

I drew many life lessons from her death. One was that my parents were totally right about that “stay out of the street” thing, and the “look both ways” thing. I did blame the victim. What kind of an idiot runs out into the street? What kind of parents let their kid play in the street? Of course, my street was much busier than her street. There were so few cars parked on the streets of my neighborhood that I was surprised there were two cars parked close enough together for that to be a thing, to run out from between two parked cars. In my brief friendship with her, I had formed no attachment. I did not feel sad about her loss. I did feel bad for Marvin. We all knew he had been playing with her that fateful day. Why would they tell us that? Who knows, maybe he told us. I had never noticed him before, but I knew him thereafter.

Upon my arrival at first grade, I discovered that there was to be no finger painting. We were too old for that. I was bitterly disappointed. Apparently, I articulated this feeling, because one day helpers came in and we got to finger paint. Trips down memory lane for a first grader.

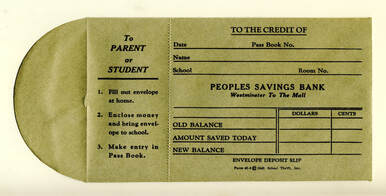

There was a school savings program. As a participant, every week, on Monday, I was given a little gray envelope to take home. My mother gave me a dime and I put in the envelope, sealed it, and filled out the information on the front, in pen. Then I brought it back to school on Tuesday and turned it in. At the end of the school year, I would get back the money, which my mother told me would be my spending money for vacation. And so I was introduced to saving up for something you want and the banking system.

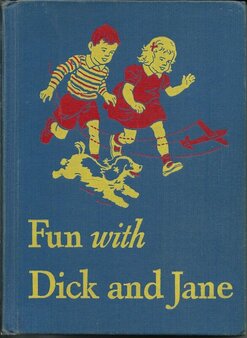

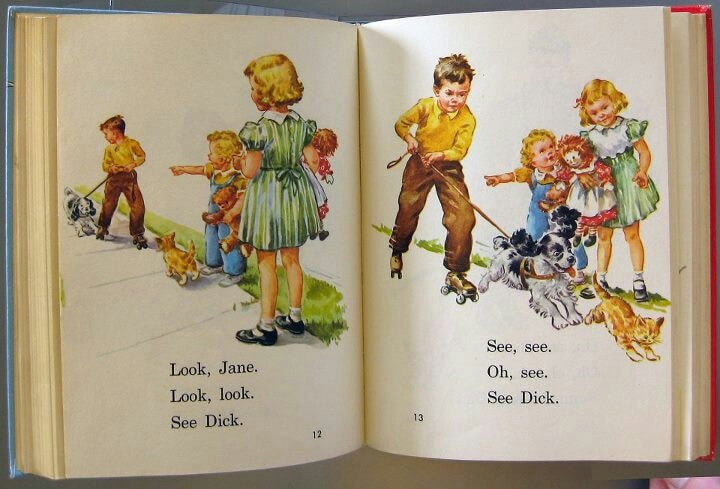

We were put into reading groups. I was in the bluebird reading group. We read from Dick and Jane readers. My parents read to me. My father taught me how to write my name before I got to school. I “read” The New Yorker cartoons. Perhaps for these reasons, I learned to read quickly. Listening to the other children stumble their way through the text in a monotone annoyed me. When my turn came to read, I read with expression and fluency.

The following year, when she got there, Jayne hated Kindergarten. She cried and had to go home on more than one occasion. I pitied her. How could she miss that there were so many more opportunities for fun. There was a playhouse! There were blocks! We planted seeds in paper milk cartons and watched them grow, sitting on the ledge of the enormous wall of windows. We painted on easels wearing Dad’s old shirt for a smock. We finger painted!

When I got to first grade, on the first day the teacher told us she had a sad announcement. Mary, one of the students who was in our Kindergarten class, had died during the summer. She was playing tag with Marvin and ran out between two parked cars into the path of an oncoming car and was killed instantly. I knew Mary. I had been to her house, about two blocks from mine, right after the Fourth of July. She showed me a mark on a support beam of a patio cover made by a pinwheel that had been driven around and around by a firework. She thought it was terrible to mar the wood like that. She was a nice ordinary little girl.

I drew many life lessons from her death. One was that my parents were totally right about that “stay out of the street” thing, and the “look both ways” thing. I did blame the victim. What kind of an idiot runs out into the street? What kind of parents let their kid play in the street? Of course, my street was much busier than her street. There were so few cars parked on the streets of my neighborhood that I was surprised there were two cars parked close enough together for that to be a thing, to run out from between two parked cars. In my brief friendship with her, I had formed no attachment. I did not feel sad about her loss. I did feel bad for Marvin. We all knew he had been playing with her that fateful day. Why would they tell us that? Who knows, maybe he told us. I had never noticed him before, but I knew him thereafter.

Upon my arrival at first grade, I discovered that there was to be no finger painting. We were too old for that. I was bitterly disappointed. Apparently, I articulated this feeling, because one day helpers came in and we got to finger paint. Trips down memory lane for a first grader.

There was a school savings program. As a participant, every week, on Monday, I was given a little gray envelope to take home. My mother gave me a dime and I put in the envelope, sealed it, and filled out the information on the front, in pen. Then I brought it back to school on Tuesday and turned it in. At the end of the school year, I would get back the money, which my mother told me would be my spending money for vacation. And so I was introduced to saving up for something you want and the banking system.

We were put into reading groups. I was in the bluebird reading group. We read from Dick and Jane readers. My parents read to me. My father taught me how to write my name before I got to school. I “read” The New Yorker cartoons. Perhaps for these reasons, I learned to read quickly. Listening to the other children stumble their way through the text in a monotone annoyed me. When my turn came to read, I read with expression and fluency.

I enjoyed the Dick and Jane illustrations excessively. I had no concept of the infusion of white cultural norms being poured into my brain. My parents did not teach their children anything about color or race except that it was unacceptable to use slur words of any kind, including “stupid.” We were not permitted to say, “shut up.” We were taught to say, “Eenie, meenie, miny, moe, catch a tiger by the toe.” I thought those were the standard words. I had no idea. What my parents did not prepare me for was the racial/cultural insensitivity that is the privilege of white people.

One day when we were washing our hands for lunch, I asked my black friend, Princess, how she could tell if her hands were clean. She looked at me like I was an idiot and said, “I can just see it.” She was not offended, or she was already dealing with micro-aggressions in the best way she knew how – to get along.

One day I found a dime on the playground. I showed the yard duty person and they gave me a pass to go up to the office to turn it in to the lost and found. What a nice adventure. I went up to the student entrance to the office, which was a Dutch door. My head was well below the height of the door, but I waited in line and was recognized. The secretary gave me one of those little gray savings envelopes and I put the dime in there, sealed it up, and filled out my information. I was hoping to get a thank you from some grateful kid, but that never happened.

One day when we were washing our hands for lunch, I asked my black friend, Princess, how she could tell if her hands were clean. She looked at me like I was an idiot and said, “I can just see it.” She was not offended, or she was already dealing with micro-aggressions in the best way she knew how – to get along.

One day I found a dime on the playground. I showed the yard duty person and they gave me a pass to go up to the office to turn it in to the lost and found. What a nice adventure. I went up to the student entrance to the office, which was a Dutch door. My head was well below the height of the door, but I waited in line and was recognized. The secretary gave me one of those little gray savings envelopes and I put the dime in there, sealed it up, and filled out my information. I was hoping to get a thank you from some grateful kid, but that never happened.

I was shorter than all the other kids. I was always the shortest one in my class. The kids called me “Shrimpy” which I hated, but I did not complain, that I recall. I was the shortest one, obviously, and they did not say it to be mean to me. I was not bullied. I was just labeled. I found the other children to be nice enough, but pretty dumb. Insipid. Uninspired. Uninspiring. Bad readers. I knew I was different.

I talked to my father about this matter one day. I told him I was different from the other kids. I wanted some advice. My father said, “Do you want to be the same as the other children at your school?” I let that sink in and then realized that, no, I did not want to be the same as the other children. I wanted to be a better reader, a faster thinker, and I liked my large vocabulary. I enjoyed speaking up and offering solutions to problems.

On that day, my life changed. I was “different”, and my father had given me permission to avoid complying with the cultural expectations of my peers, that I dumb myself down. That was the first day of my queer life, in which I resisted placement in the box in which the culture expected to imprison me. Before I knew I was doing it, I resisted gender classification. When I learned that “he” was the universal pronoun, I realized that while it was traditional, and perhaps a practical solution, it was wrong.

My parents were intellectuals and they were both non-conforming, so they modeled for me an independent approach to life. My reading was not censored; I was permitted to read any texts in the house. I read The New Yorker backwards to front, in search of the cartoons. I stopped to read shorter passages, which would often be poetry and quotes from literature in larger pieces. I read slim poetry books from the University of Washington where my father was an undergraduate and then graduate student. Some of the materials were not age appropriate, but my parents encouraged me to ask questions. I didn’t have many.

On the last day of first grade, someone came from the office and called a list of students to go to the principal’s office. I was one of them. I was horror stricken. What could I possibly have done to warrant this dreadful happenstance? Two other children and I were escorted to the waiting room where we sat on a bench and waited for an eternity. Perhaps it was only a couple minutes, but I was beside myself with embarrassment.

Finally, the principal came out of his office. He had little gray banking envelopes in his hand. He read the names and handed them out. It was the dime I turned into the lost and found! No one had claimed it!

Oh frabjous day! Callooh Callay!

I talked to my father about this matter one day. I told him I was different from the other kids. I wanted some advice. My father said, “Do you want to be the same as the other children at your school?” I let that sink in and then realized that, no, I did not want to be the same as the other children. I wanted to be a better reader, a faster thinker, and I liked my large vocabulary. I enjoyed speaking up and offering solutions to problems.

On that day, my life changed. I was “different”, and my father had given me permission to avoid complying with the cultural expectations of my peers, that I dumb myself down. That was the first day of my queer life, in which I resisted placement in the box in which the culture expected to imprison me. Before I knew I was doing it, I resisted gender classification. When I learned that “he” was the universal pronoun, I realized that while it was traditional, and perhaps a practical solution, it was wrong.

My parents were intellectuals and they were both non-conforming, so they modeled for me an independent approach to life. My reading was not censored; I was permitted to read any texts in the house. I read The New Yorker backwards to front, in search of the cartoons. I stopped to read shorter passages, which would often be poetry and quotes from literature in larger pieces. I read slim poetry books from the University of Washington where my father was an undergraduate and then graduate student. Some of the materials were not age appropriate, but my parents encouraged me to ask questions. I didn’t have many.

On the last day of first grade, someone came from the office and called a list of students to go to the principal’s office. I was one of them. I was horror stricken. What could I possibly have done to warrant this dreadful happenstance? Two other children and I were escorted to the waiting room where we sat on a bench and waited for an eternity. Perhaps it was only a couple minutes, but I was beside myself with embarrassment.

Finally, the principal came out of his office. He had little gray banking envelopes in his hand. He read the names and handed them out. It was the dime I turned into the lost and found! No one had claimed it!

Oh frabjous day! Callooh Callay!

A note: all the photos are just grabbed from the internet to provide context, unless labeled. They are the best approximates of what I am trying to describe.