How To and How NOT To Teach Reading

by Shelley Pineo-Jensen, Ph.D.

I woke up at six am out of a nightmare. In my dream, I was presenting an in-service to a large group of teachers, using a slide show and my clicker/laser pointer. This was not unlike the work I did when I was a taking a Ph.D. in Educational Methodology, Policy, and Leadership at University of Oregon in 2013, as a teaching assistant for various classes including graduate level statistics for three years and at a presentation of survey and data analysis for a large school district in Oregon as part of my study of labor of unions. The slides in the dream were wonky, spread sheets of data, graphics of data analysis . . .

Unlike the respectful graduate students who listened to my lectures at UO, and the polite teachers at that school district, the teachers in my dream heckled me. One yelled out something about if I had done any preparation at all for the presentation. Another loudly questioned the relevance of the material. I left my prepared notes and moved away from the side of the room where I did not block my slides and clicked my slides forward and pointed at my slides with my little laser beam. I moved to the front and center of the room to speak directly about my teaching experience, my relevance.

Then I started (startled?) awake, with a driving urge to find an audience for what I know about teaching children to read. I don’t think this article on my website, and the blog post that points to it, and the Facebook posts and story that will publicize it, will bring in the audience I seek, which is teachers and educational decision-makers, but I write it up, none-the-less. Perhaps someone will find these ideas useful.

I woke up at six am out of a nightmare. In my dream, I was presenting an in-service to a large group of teachers, using a slide show and my clicker/laser pointer. This was not unlike the work I did when I was a taking a Ph.D. in Educational Methodology, Policy, and Leadership at University of Oregon in 2013, as a teaching assistant for various classes including graduate level statistics for three years and at a presentation of survey and data analysis for a large school district in Oregon as part of my study of labor of unions. The slides in the dream were wonky, spread sheets of data, graphics of data analysis . . .

Unlike the respectful graduate students who listened to my lectures at UO, and the polite teachers at that school district, the teachers in my dream heckled me. One yelled out something about if I had done any preparation at all for the presentation. Another loudly questioned the relevance of the material. I left my prepared notes and moved away from the side of the room where I did not block my slides and clicked my slides forward and pointed at my slides with my little laser beam. I moved to the front and center of the room to speak directly about my teaching experience, my relevance.

Then I started (startled?) awake, with a driving urge to find an audience for what I know about teaching children to read. I don’t think this article on my website, and the blog post that points to it, and the Facebook posts and story that will publicize it, will bring in the audience I seek, which is teachers and educational decision-makers, but I write it up, none-the-less. Perhaps someone will find these ideas useful.

I started teaching in a small K-8 district in an impoverished area, at a middle school: 8th grade in the-class-from-hell that frequently welcomes teachers to the profession. A teacher quits or retires, and the most senior teacher gets right of first refusal. Working its way down through seniority, teachers move to the most, and then the more, and then the somewhat more, desirable positions, whatever that means to them, until finally, at the bottom of the list, the teacher with the least seniority gets the choice to move, and she does, because she is currently teaching the-class-from-hell. Then the district hires a new teacher, who gets this sorry assignment.

In my case, it was an 8th grade class that was “self-contained” meaning that while the other 8th graders rotated through blocks of classes, my students stayed with me all day. These were students who were not considered capable of moving around campus with the other middle schoolers. They needed more support. A full third of my class were receiving “services” and were therefore gone for parts of the day. It was a grueling way to start my teaching career and for three months I kept my head down and redid my lesson plans daily. Finally, I looked up, so my husband tells me, and said, “I think I am going to be able to do this.”

Many of my students were reading at a second or third grade level. I did not teach them how to read. I didn’t know how to do that.

The next year the school did away with the self-contained 8th grade classroom. I started teaching fifth grade at the middle school. Due to overcrowding, two classes of fifth graders were housed at the middle school. I was given training in Accelerated Reading (AR). This system drives reading practice, which is the most important predictor of increased reading ability. During reading practice, students read from a book within their “zone of proximal development” (ZPD – by way of Vygotsky). Then they take a down and dirty test on the computer which gives them a score based on these things: Did they read the book? Did they understand the book? Every six weeks everyone in the class takes a “Star Test” which assesses reading level. Students then have their ZPD adjusted.

Many of my students were reading at a second or third grade level. I did not teach them how to read. I didn’t know how to do that.

The next year the school did away with the self-contained 8th grade classroom. I started teaching fifth grade at the middle school. Due to overcrowding, two classes of fifth graders were housed at the middle school. I was given training in Accelerated Reading (AR). This system drives reading practice, which is the most important predictor of increased reading ability. During reading practice, students read from a book within their “zone of proximal development” (ZPD – by way of Vygotsky). Then they take a down and dirty test on the computer which gives them a score based on these things: Did they read the book? Did they understand the book? Every six weeks everyone in the class takes a “Star Test” which assesses reading level. Students then have their ZPD adjusted.

After two years of teaching fifth grade, the student population of the district shifted, and I was moved over to a regular elementary school to continue teaching fifth grade. Our district divided the student population by grade groupings, with the aforementioned middle school, a school housing K-2, and my school of third through fifth grades. This grouping system was perfect for the Success for All (SFA) reading system we used. Success for All is a reading program that sorts students by reading level. Students are taught to read at their operational reading level, regardless of their chronological age. Every six weeks, all the students were assessed for operative reading level and regrouped.

We had great success raising student test scores, particularly for our English as a Second Language (ESL) students. Some teachers hated it, because they did not want to teach a group of fifth graders reading at a second-grade level. They did not like the behaviors of “big” students who were reading at such a low level. They liked their second-grade level readers to be sweet little seven-year-olds, not big nasty ten-year-olds with behavior problems.

The first year I taught random reading level groups and learned the system, but as my colleagues got to know me better, I ended up with the highest-level reading groups, much the same as when we started a GATE (Gifted and Talented Education) class at our school once a week for half a day; it was offered to me. But I digress.

We had great success raising student test scores, particularly for our English as a Second Language (ESL) students. Some teachers hated it, because they did not want to teach a group of fifth graders reading at a second-grade level. They did not like the behaviors of “big” students who were reading at such a low level. They liked their second-grade level readers to be sweet little seven-year-olds, not big nasty ten-year-olds with behavior problems.

The first year I taught random reading level groups and learned the system, but as my colleagues got to know me better, I ended up with the highest-level reading groups, much the same as when we started a GATE (Gifted and Talented Education) class at our school once a week for half a day; it was offered to me. But I digress.

When No Child Left Behind (NCLB) hit, Robert Slavin’s Success for All was tossed in the dumpster, because it did not teach to grade level standards. The absurdity of this decision haunts me to this day. Half my students showed up to my fifth-grade classroom reading at a second-grade level, but I was expected to teach them “inference” and NOT to teach them to read. We no longer had access to the Slavin resources – reading materials organized by reading level with tests created by graduate students of Slavin at Johns Hopkins University.

The district had built a new school and sorting by grade levels was inconvenient to bussing, so I now taught in a regular K-5 school. The fifth-grade team was distributed across three schools and our team planning was constrained. The resource teacher and the other fifth grade teacher and I got permission from our principal to do our own re-grouping for reading during the two and a half hours of reading instruction daily that the district was now mandating.

The resource teacher got the BBs (Below Basic) students, who were all identified with IEPs, and my dear colleague Amy (not her real name) got the Bs (Basic) readers, and I got the Proficient and Advanced (the at- and the above-grade level) students. This was a tough grouping – the range of reading ability was huge, but it was nowhere near as difficult as Amy’s challenge. Her students, a classful of them, were reading at second, third, and fourth grade reading levels but were expected to learn the fifth-grade standards, all while literally not being able to read the mandated fifth-grade Houghton Mifflin textbook.

Here is one of the insane parts of what happened. The children listened to a CD provided by the publisher of a woman reading the text to them. Then they worked on worksheets on the standards . . . you know . . . inference. For two and a half hours every day, we did NOT teach them to read, so they could take a standards-based test in April that they were not going to be able to read. You cannot make this stuff up.

I also taught a reading syllabification program that was excellent . . . REWARDS? Not sure of the acronym of that program. It was brutally repetitive, but it worked like gang busters.

The district had built a new school and sorting by grade levels was inconvenient to bussing, so I now taught in a regular K-5 school. The fifth-grade team was distributed across three schools and our team planning was constrained. The resource teacher and the other fifth grade teacher and I got permission from our principal to do our own re-grouping for reading during the two and a half hours of reading instruction daily that the district was now mandating.

The resource teacher got the BBs (Below Basic) students, who were all identified with IEPs, and my dear colleague Amy (not her real name) got the Bs (Basic) readers, and I got the Proficient and Advanced (the at- and the above-grade level) students. This was a tough grouping – the range of reading ability was huge, but it was nowhere near as difficult as Amy’s challenge. Her students, a classful of them, were reading at second, third, and fourth grade reading levels but were expected to learn the fifth-grade standards, all while literally not being able to read the mandated fifth-grade Houghton Mifflin textbook.

Here is one of the insane parts of what happened. The children listened to a CD provided by the publisher of a woman reading the text to them. Then they worked on worksheets on the standards . . . you know . . . inference. For two and a half hours every day, we did NOT teach them to read, so they could take a standards-based test in April that they were not going to be able to read. You cannot make this stuff up.

I also taught a reading syllabification program that was excellent . . . REWARDS? Not sure of the acronym of that program. It was brutally repetitive, but it worked like gang busters.

So, the point of this story is that two times in my elementary school teaching career, I got phone calls from the middle school asking what I was doing differently from my peers, in teaching reading. The test scores of my students had gone up more than those of my peers’ students.

I really had to rack my brain the first time I met this question but finally I figured it out. I was teaching the hell out of Accelerated Reader. This is the heart of the story – what I did differently, using Accelerated Reader, that allowed my students to improve their reading level faster than other students in my district.

Some of us teachers tried to get the school library to be organized by the reading level of the books, but the Dewey Decimal brigade stopped that. God forbid students be able to easily find a book at their reading level when we could put all the authors in ABC order. Order! There must be order!

So I built my own library in the classroom. I used most of my classroom money for books. I bought books on my own dime. I got books at garage sales. I even contributed some of my own books, my children’s books, and they were trashed in the process. The books were in tubs by reading level. Only books with AR tests were included in this system.

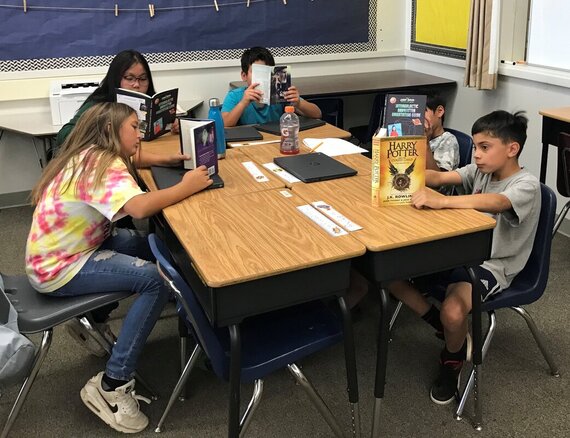

AR time was daily – right after lunch the kids came into a time of quiet reading. We moved all our desks out of groups into a random scatter, so that the distractable had fewer distractions and the busy bodies had less chance of an audience. I played cool jazz and classical music.

Students were allowed to get up to take a test and shop for a new book. Some kids had permission to go to the library to get a book, but mostly I just kept them in the room, since they were unsupervised in the library and in the hall on the way there and back, and, you know the library is a wonderous place and once they were there, they didn’t come back right away, meaning lost reading time. It was more of a reward than a practice. Plus, the librarian, while not outright hostile, was untrained (I think it was one of the yard duty women) and didn’t like having unsupervised students in there.

But here is the secret sauce – My sister Jayne, who was an award-winning high school teacher, shared a huge AR tip with me – she didn’t wait for the six-week Star Test to raise her students’ ZPD range. If they scored 90-100% on a book, she raised the range right then. What was this blasphemy? But she swore by it so I tried it. What a revelation.

So, I made an index card for each child. They wrote the name of the book and its reading level on a line. When they finished a test, they would get me, and I would see their score and write it on the card. If they got 80-100% (lower-level books only have 5 questions on the test, so it had to be 80%, unlike my sister’s 90%) three times in a row, I raised their ZPD by 0.1.

Students found it very validating to have their ZPD level raised. It meant that they could move up to the next box of books on the bookshelves. It was a huge motivator that was totally intrinsic.

And that’s the magic and it worked. I never told the principal about my bastardization of AR, because I knew he would make up a rule that I couldn’t. But my parade of student teachers knew. Perhaps these ideas live on, hiding out somewhere in the fucked-up standards-based educational system that we have de-evolved to in America.

I really had to rack my brain the first time I met this question but finally I figured it out. I was teaching the hell out of Accelerated Reader. This is the heart of the story – what I did differently, using Accelerated Reader, that allowed my students to improve their reading level faster than other students in my district.

Some of us teachers tried to get the school library to be organized by the reading level of the books, but the Dewey Decimal brigade stopped that. God forbid students be able to easily find a book at their reading level when we could put all the authors in ABC order. Order! There must be order!

So I built my own library in the classroom. I used most of my classroom money for books. I bought books on my own dime. I got books at garage sales. I even contributed some of my own books, my children’s books, and they were trashed in the process. The books were in tubs by reading level. Only books with AR tests were included in this system.

AR time was daily – right after lunch the kids came into a time of quiet reading. We moved all our desks out of groups into a random scatter, so that the distractable had fewer distractions and the busy bodies had less chance of an audience. I played cool jazz and classical music.

Students were allowed to get up to take a test and shop for a new book. Some kids had permission to go to the library to get a book, but mostly I just kept them in the room, since they were unsupervised in the library and in the hall on the way there and back, and, you know the library is a wonderous place and once they were there, they didn’t come back right away, meaning lost reading time. It was more of a reward than a practice. Plus, the librarian, while not outright hostile, was untrained (I think it was one of the yard duty women) and didn’t like having unsupervised students in there.

But here is the secret sauce – My sister Jayne, who was an award-winning high school teacher, shared a huge AR tip with me – she didn’t wait for the six-week Star Test to raise her students’ ZPD range. If they scored 90-100% on a book, she raised the range right then. What was this blasphemy? But she swore by it so I tried it. What a revelation.

So, I made an index card for each child. They wrote the name of the book and its reading level on a line. When they finished a test, they would get me, and I would see their score and write it on the card. If they got 80-100% (lower-level books only have 5 questions on the test, so it had to be 80%, unlike my sister’s 90%) three times in a row, I raised their ZPD by 0.1.

Students found it very validating to have their ZPD level raised. It meant that they could move up to the next box of books on the bookshelves. It was a huge motivator that was totally intrinsic.

And that’s the magic and it worked. I never told the principal about my bastardization of AR, because I knew he would make up a rule that I couldn’t. But my parade of student teachers knew. Perhaps these ideas live on, hiding out somewhere in the fucked-up standards-based educational system that we have de-evolved to in America.

Reading practice, at school. Reading inside the zone of proximal development. Constant assessment without punishment or stress. Continual feedback from a patient teacher who cares about the student and the student’s individual academic growth.

And that is what I wanted to tell the teachers who rejected me in my dream.

And that is what I wanted to tell the teachers who rejected me in my dream.